Mauritius during World War I

World War 1, known as the Great War, officially commenced on 28 July 1914 and lasted four years until 11 November 1918. The United Kingdom entered the Great War on 4 August, 1914, which in turn implicated all British Allied Nations, of which Mauritius was one of the Indian Ocean islands to show allegiance. At the outbreak of First World War, Mauritius had a population of 372,000. It was largely made up of Indo-Mauritians, the descendants of Indian indentured labourers, and Creoles, the descendants of African and Madagascan slaves, as well as communities of Franco-Mauritians of French ancestry and British colonists. Before the war, Mauritius was defended by around 1,000 British and Indian troops, who were based in the Imperial garrison. On August 6, 1914 martial law was promulgated in Mauritius as in all British colonies. Most of the provisions made concerned justice, property and defence of the territory. The government could order a person for trial in a civil or military court to seize private property or even agricultural property. Early in August, proclamations in respect of the war were published in the Official Journal:

Proclamation number 33 is addressed to all population by announcing the alarms in the event of an attack on the sea: by day, a blue flag hoists on the Mountain of Signals and at night two green flags. Night and day, cannon fire from the Citadel will serve as an alert. As soon as there is one, the troops, firefighters, police and all those concerned by the defense of the country will return to their posts. If the signal is given at night, the inhabitants of the capital will have to stay at home and, to facilitate the movement of all those concerned with the defense, the inhabitants were requested to light a lamp near the windows facing the street. In the event of bombardment of the city, the inhabitants of Port Louis will have to go to the rear of Vallee-des-Pretres to take shelter.

Mauritian in World War I

The contribution of Mauritius to the Allied war effort has been much neglected in the historiography of the Great War. At the outbreak of hostilities, the population of the multi-ethnic island rallied enthusiastically behind the Allies. Yet the military effort was never commensurate with the size and importance of the colony.

On August 5, 1914, with the official announcement of the start of hostilities in Europe, there was overwhelming enthusiasm in Mauritius for the Allies. The predominantly Franco-Mauritian colonial elite was already considering how to contribute to the war. Moreover, upon the announcement of the declaration of war in “Le Mauricien” on August 6, 1914, a large crowd moved towards the Hôtel du Government. Already, the Consulate of France was underlining the creation of a volunteer militia to be assigned to the defense of the island.

In the days that followed, many volunteers showed up to serve in Lord Kitchener’s army. Five were chosen to fight at the front in England and three others were enlisted in the French army. As for the rest of the volunteers, government officers, they could not leave because the demands of the public service did not allow it. So the majority of them enlisted in the Volunteer Force.

In addition, several Mauritian students, residing in England and France, without hesitation joined the armies within the Volunteer Force. Several notables of the colony under the leadership of Dr de Chazal subscribed sufficient funds to pay for transport and expenses for those wishing to travel to Europe to fight in the Allied forces. In the first two years, more than 1,500 men in all were recruited for the battalion service in Mesopotamia (Irak) which was named the Mauritius Labour Battalion. Most of these men were from Indo-Mauritian, Sino-Mauritian and Creoles origin. Some were even from Rodrigues Island.

These men worked as drivers, stevedores, carpenters, cooks and tradesmen. Some sixty men of the Mauritius Labour Battalion died due to illness while in service abroad. Many of them are buried in Basora Irak and some in other places. The Victory medal 1914 – 19 was awarded to several Mauritians who served in the WW1 including those of the Mauritius Labour Battalion.

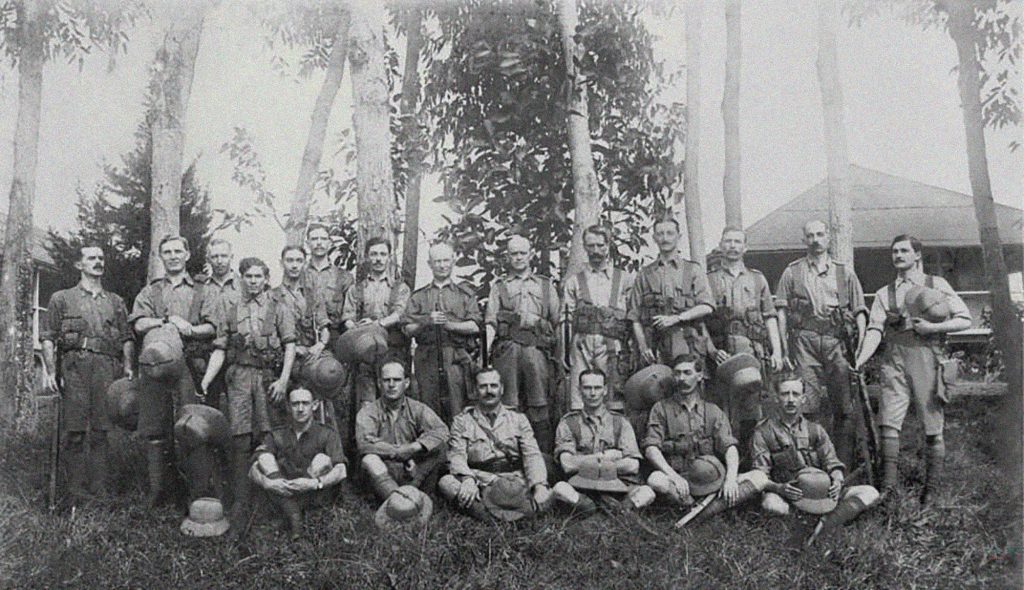

On December 21, 1918, the British Governor declared to the Secretary of State that there was a strong and genuine desire on the part of many Mauritians such as MPs M. Martin, E. Nairac, Duclos, E. Sauzier and others belonging to the colonial elite to represent the island on the battlefields. He wanted a contingent to be created to join the army. During the first two years of the conflict, the local press continued to deplore the fact that the Mauritians had been prevented from participating in the fighting in Europe by Sir John Chancellor and General Simpson, which was an insult to their self-esteem. In 1917, a contingent of volunteers was finally recruited. However, no contingent of combatants was sent to the front. A number of Mauritians and also Rodriguans volunteered left at their own expense to integrate the British or French armies – including the imperial or colonial regiments – generally as officers. This corps of volunteers included several notables including doctors Arthur Célestin, Clifford Mayer and Raoul Leblanc. Twenty-five were sent at the initiative and at the expense of the De Chazal Committee, founded by Dr Lucien de Chazal. They had been preceded by Mauritian students who were in Europe for university studies. Robert Edward Hart in his book The Mauritians Volunteers in the Armies 1914-1918 gives the names of 520 volunteers. They were all people from the Franco and Anglo- Mauritian communities. Among them are a large number of former students of the Royal College of Curepipe. Of these, 265 served in the Metropolitan or Colonial forces of England, including the Royal Air Force and the Royal Navy, 92 in the French armies and 4 in the American ranks. Many received military honors and others died in combat. On the War Memorial erected in front of the Royal College of Curepipe, the names of 48 of these Mauritian war heroes are inscribed.

Mauritius Defence Force World War I

In October 1915, an act was passed to recruit a local defence force (and in 1916, a little over 500 recruits joined the Mauritius Volunteer Force). They formed three companies of infantry, a company of artillery, a company of engineers and an ambulance corps. To encourage further enrollment some members of the Legislative Council joined the Mauritius Volunteer Force as officers. They were offered the grade of lieutenant on joining. This allowed the regular army troops in the garrison to be deployed where they were most needed, with the exception of the 59th Royal Garrison Artillery and the 25th Company, Royal Engineers, who stayed to bolster the volunteer force. In 1915, a naval wireless station was built on a site in Rose Belle. At the start, many Mauritians wanted to fight in the British forces but encountered reluctance from the authorities. The Mauritians either volunteers or engaged ones joined the battle with great patriotic enthusiasm. Like all other soldiers, they thought the war would be short and easy to win. Present in the land, naval and air forces, they fought in all army corps: infantry, artisans, navy and aviation.

Some Mauritian pilots distinguished themselves even in the very first air battles of French and British military history. The posting of the committed Mauritians — volunteers or mobilized — depended on their nationality, community affiliation, their motivation or their country of residence at the time of entry into the war. Mauritians joined the French army as volunteers or by obligation in the event of dual nationality. Mauritians were also enlisted into the Australian, Canadian, New Zealand, South African, Indian and even American forces. In 1917 a labour battalion was raised and over 1,500 Mauritians served in Mesopotamia . A further 520 Mauritians joined the British and French Armies, and close to 200 Mauritians joined the Merchant Navy. The Mauritians followed their regiment on all fronts except the Eastern front where they were fighting the Russian forces. They were often at the forefront of the great battles from Belgium to East Africa and from Verdun to Kut-el-Amara. The following gallantry medals were awarded to men enlisting from Mauritius: one Distinguished Service Cross, 12 Military Crosses, two Distinguished Conduct Medals, four Military Medals, 19 Croix de Guerre, one Medaille Militaire, one Medaille d’Honneur and three Legions d’Honneur.

The Great War Tribute

“Most of the Mauritian families have sons fighting on the different battlefields of the present war; some of them have already laid down their lives for king and mother-county, and not a few have won the V.C. and the M.C., amongst these are Lieutenant Cyril Anderson- Blackburn, Mayer, Finniss, and Kenneth Paddle.”

Source: The Epidemics of Mauritius (published in 1918)